In an essay at The New York Times online, We’re All Conservatives Now, Stanley Fish seeks to reconcile the concerns of both Right and Left about the American university. Contrasting the complaints of the right wing David Horowitz to the the left wing visions offered in the recent “Academic Freedom in the Post-9/11 Era” (edited by Edward J. Carvalho and David B. Downing, and bringing together the righteous and the repellent), Fish finds a commonality of esteemed virtues.

What this means is that despite the point-counterpoint accusations of betrayal, corruption and anti-intellectualism (charges hurled by each party at the other), the left and the right are after the same thing, and it turns out to be just what Immanuel Kant urged in his essay “What is Enlightenment?” (1784) when he answered his title question by declaring that “enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity,” an immaturity marked by his reliance on the pre-packaged guidance of others as opposed to the exercise “of his own rational capacities.”

Mankind, says Kant, must constantly labor to “expand its knowledge . . . to rid itself of errors, and generally to increase its enlightenment.” No one in the Carvalho-Downing volume or on Horowitz’s side of the street would dissent.

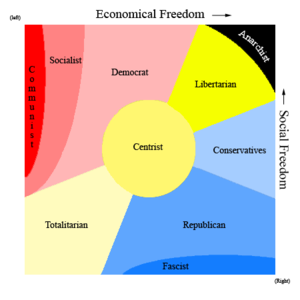

This is, unfortunately, a little too easy. Sure, it is to the good that both sides can agree at this level of generalization. There are, in fact, extreme elements on the Right, still, who find intellectual virtue in pre-Enlightenment religious doctrine and in the volk. There are extremes on the Left, rationalizers of the Islamist critique of the West, who now challenge Enlightenment principles. But it is in the application of these general principles of education that the two sides disagree, and it is at the level of application that we live. Fish offers, insufficiently examined, the perfect example.

But the right is right to point out that the faculty who work within these ever-more-pinched spaces are predominantly liberal and have over the years created “new inter-disciplinary fields whose inspirations were ideological and closely linked to political activism” (Horowitz, “Reforming Our Universities”). (Of course, the fact that a course of study was born out of ideological/political concerns doesn’t mean that instruction in its materials is necessarily ideological and political; any subject matter, whatever its origin, can be taught from an appropriately academic perspective.)

What exactly is meant by “new inter-disciplinary fields whose inspirations were ideological and closely linked to political activism”? Most obviously, this would mean various distinct fields of cultural study, e.g. African-American studies, Latino Studies, and gender studies, but also, more generally, culture studies itself and postcolonial studies, as well as literary and critical theory. Fish is right to make the point that “the fact that a course of study was born out of ideological/political concerns doesn’t mean that instruction in its materials is necessarily ideological and political” – but what exactly does it mean for the instruction in a field of study born of ideology not to be taught ideologically? In the most neutral sense, this might mean that instruction would acknowledge the ideologically contested nature of the field and present a course of study that explored the range of contested issues. That would be a perfectly legitimate approach, though it is difficult to imagine at the college level an instructor sufficiently trained and expert in the field of gender studies, for instance, who would not, by that virtue, be someone who embraced rather than disputed or was even neutral regarding the field’s inciting ideas.

Here is a different sense of instruction that is not, in Fish’s words, “necessarily ideological and political,” that can be offered “from an appropriately academic perspective.” I have made the point a number of times recently that one need not be, strictly speaking, a postcolonialist – in the most commonly expressed, fully ideological sense of the term – in order to recognize a range of historical truths about the colonial era and the necessity of a postcolonial understanding and vision of world affairs. One does not need be a Marxist (despite the simpleminded propagandizing of a Glenn Beck or Rush Limbaugh) to recognize a range of legitimacy in the Marxist critique of capitalism. One can even still be a capitalist. Neutral does not mean without perspective. The truth is a perspective, in contrast to the lie; perspective does not necessarily mean bias or completely subjective relativity. It is a fundamental error of journalistic practice to believe that reportorial “objectivity” requires that the political corruptions or falsifications of the tyrant – or even of the democratically-elected sanctioner of torture – be reported on an equal basis with the known truth, without “perspective,” or without pointed contrast to established and well-supported political and moral virtues.

It is the political argument – the ideological argument – of the Right, to claim that only the fields of academic study that existed before some imaginary demarcation in time are non-ideological, representative of a halcyon era of pure education. To claim that the special nature of specifically African-American history and culture in the United States – previously unintegrated into general study outside of its marginalization in victimhood – does not warrant, therefore, a specialized field of study by virtue of that prior exclusion, and the reasons for it – that is not to oppose ideologically-driven education. That is too promote it. The opposition to so obviously, conceptually well-founded a field of study is itself profoundly ideological. The pretense by the Right that the world, the academic world, before the 1960s was non-ideological is ideological.

Does the arguably ideological nature of both sides of the divide mean they are equal – merely self-limiting perspectives without any claim to truth? No. These are the disputes of mere decades. The history of civilization has included combat on the field and the contest of ideas. The very fact of the contest does not make both sides the same or equal. The judgments of reason and experience will be made over time. Once, to be black in this country was to be discounted and inferior. Once, to be gay was to be hidden from view and inferior, in the military too. As of yesterday, that is no longer so, and never will be again, though there will always remain those who contest these changes and claim therefore they are not true – that those who seek not to stand still, but in Kant’s words, to rid the world “of errors, and generally to increase its enlightenment” are ideological.

AJA

Related articles

- Cassirer and the Enlightenment (inpropriapersona.com)

- Ideological Archeology: Countering Kant (III) (politeia-station.net)

- Nation, Culture, and Identity (sadredearth.com)

- Tom Silva: Kant on the Campaign Trail (capitolhillblue.com)

- Ideological Archeology: The Counter-Enlightenment (I) (politeia-station.net)

- Ideological Archeology: Rousseau (II) (politeia-station.net)

- *VIDEO* Reforming Our Universities: The Campaign For An Academic Bill Of Rights (thedaleygator.wordpress.com)

- Philosophy of Science (socyberty.com)